Justice Jamal Mandokhail: The real issue arose after the amendment to the original Army Act

Misuse of the blasphemy law had started, and to prevent its misuse, investigation was assigned to an SP-level officer

If a soldier commits a crime and a common man commits the same crime, how can their trials be held in different courts? – Justice Ameen-ud-Din Khan

A law cannot be declared void merely because of its misuse – Chief Justice of the Constitutional Bench during the hearing

Islamabad (Web News)

The head of the constitutional bench of the Supreme Court of Pakistan, Justice Ameen-ud-Din Khan, stated that if a law is being misused, it cannot be declared void solely on that basis. The misuse of the blasphemy law had started, and to prevent its misuse, investigation was assigned to an SP-level officer. He questioned how it is possible that if a soldier commits a crime and a common man commits the same crime, their trials are conducted in separate courts. Meanwhile, Justice Jamal Mandokhail remarked that the real issue arose after the amendment to the original Army Act. He pointed out that in 1967, the President individually issued an ordinance and amended the law.

He questioned whether a person who is not part of the army can come under the jurisdiction of a military court merely because of committing a crime. He also noted that religious edicts (fatwas) are issued by the same people, while governments come and go. Justice Muhammad Ali Mazhar remarked that India’s court-martial system is similar to Pakistan’s, with the only difference being the right to appeal. Many crimes fall under court-martial jurisdiction. Justice Syed Hasan Azhar Rizvi stated that some of Pakistan’s enemy countries use civilians, and if sections 2(1)(d)(1) and 2(1)(d)(2) of the Army Act are declared void, then those working for hostile foreign agencies would not be subject to military trials. He asked where their trials would then take place.

Justice Musarrat Hilali stated that Zia-ul-Haq himself was the judge in the F.B. Ali case and later pardoned him. She speculated whether Zia-ul-Haq later apologized to F.B. Ali for his mistake. Justice Naeem Akhtar Afghan noted that the decision in the F.B. Ali case stated that there was no violation of fundamental rights.

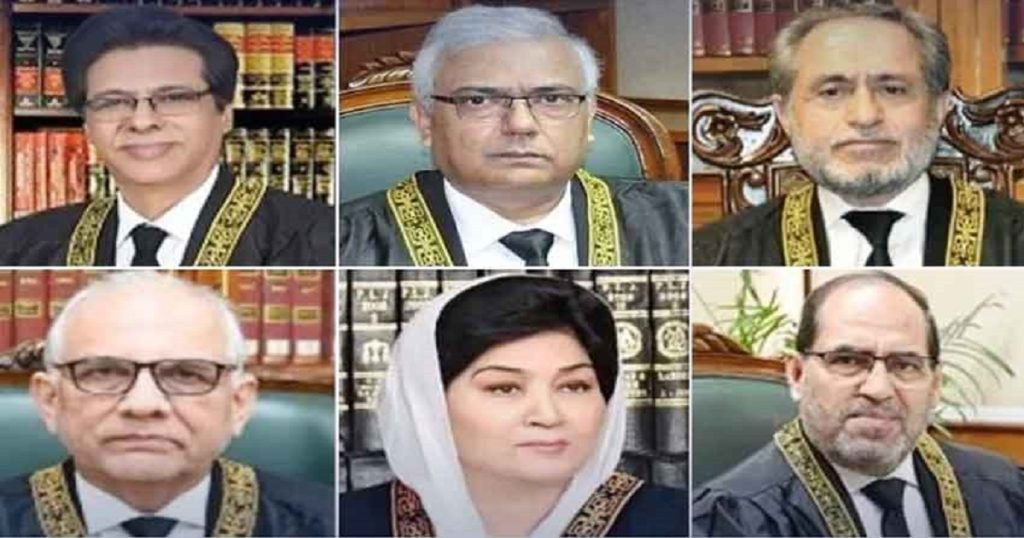

A seven-member constitutional bench of the Supreme Court, led by senior judge Justice Ameen-ud-Din Khan and including Justices Jamal Khan Mandokhail, Muhammad Ali Mazhar, Syed Hasan Azhar Rizvi, Musarrat Hilali, Naeem Akhtar Afghan, and Shahid Bilal Hassan, heard 38 review petitions challenging the trial of civilians in military courts.

Lawyer Salman Akram Raja, representing Junaid Razzaq and others, continued his arguments, stating that the F.B. Ali case was decided under the 1962 Constitution. Justice Jamal Khan Mandokhail observed that the F.B. Ali case was limited to whether the federal government could legislate or not. He inquired about the powers of military courts under the Army Act and whether a non-military person could be subjected to military court jurisdiction based on their crime alone.

Justice Muhammad Ali Mazhar questioned why the Army Act was upheld in the F.B. Ali case. Justice Syed Hasan Azhar Rizvi asked whether F.B. Ali was in service at the time, to which Salman Akram Raja responded that he was not. Raja explained that in the F.B. Ali case, the Supreme Court ruled that civilians could be tried in military courts, but they would still have fundamental rights, whereas active-duty military personnel would not enjoy those rights.

Justice Jamal Mandokhail questioned why, under Article 8(3) of the Constitution, a law was enacted that deprived armed forces personnel of fundamental rights. He also asked whether a military officer who commits a crime while off duty would be considered a military personnel or a civilian. Justice Naeem Akhtar Afghan pointed out that it is the commanding officer’s discretion whether to conduct a military trial or refer the case to a civilian court.

Justice Jamal Khan Mandokhail reiterated that the real issue arose after amendments to the original Army Act. He noted that in 1967, the President issued an ordinance and amended the law. Justice Naeem Akhtar Afghan stated that the F.B. Ali case decision concluded that there was no violation of fundamental rights.

Salman Akram Raja argued that the court had ruled that fundamental rights must be provided and that the trial had not violated fundamental rights. He explained that the F.B. Ali case discussed Section 2(d)(1) of the Army Act and that the Supreme Court ruled that the ordinance issued by the President was valid and could be reviewed under fundamental rights.

Justice Jamal Mandokhail asked how the term “collusion” was defined in the F.B. Ali case. Salman Akram Raja replied that collusion must be related to national defense and influencing a military officer. He criticized how the F.B. Ali case had been interpreted to justify separate military courts.

Justice Naeem Akhtar Afghan remarked that today, sections 2(1)(d)(1) and 2(1)(d)(2) are being applied. Justice Ameen-ud-Din Khan told Salman Akram Raja that he was arguing against the main decision. Salman Akram Raja responded that there was also a decision by Justice Ayesha Malik on the matter.

Justice Muhammad Ali Mazhar questioned why sections of the Army Act were declared void. Salman Akram Raja explained that appeals are filed against verdicts, not reasons, and that courts can maintain the operative part while altering the reasoning. He emphasized that the case before the bench involved Articles 10-A and 175 of the Constitution.

Justice Jamal Mandokhail noted that in 1968, an ordinance was issued that granted judicial powers to a Balochistan tehsildar, which was later overturned by the Supreme Court in the Azizullah Memon case. He pointed out that even after the 1973 Constitution, this system continued for 14 years.

Salman Akram Raja argued that when Article 175(3) was introduced in 1987, the law changed. He contended that if the court upheld Justice Ayesha Malik’s decision on Article 10-A, it would be a victory for his case. Similarly, if the court ruled that a court cannot be established outside the scope of Article 175(3), it would still be a victory.

He also noted the irony that Brigadier (Retd.) F.B. Ali was court-martialed and sentenced under military law by Zia-ul-Haq, but when Zia became Army Chief, he pardoned him. Justice Jamal Mandokhail speculated that perhaps Zia-ul-Haq later realized he was wrong. Salman Akram Raja added that F.B. Ali later moved to Canada and took a job in security.

Justice Musarrat Hilali remarked that Zia-ul-Haq himself was the judge in the F.B. Ali case and later pardoned him. “Is it possible that Zia-ul-Haq later apologized to F.B. Ali, admitting he had made a mistake?”

Salman Akram Raja stated, “The 1962 Constitution starts with Field Marshal Ayub Khan granting himself powers. Articles were inserted during that time, and fatwas were issued stating that fundamental rights do not exist in Islam.”

Justice Jamal Khan Mandokhail commented, “The people issuing fatwas remain the same; only governments change.”

Salman Raja responded, “That is why Habib Jalib wrote the poem Main Nahin Manta during Ayub Khan’s era. After a one-and-a-half-year-long movement, fundamental rights were eventually recognized.”

He further argued, “Between 1977 and 1980, the Balochistan High Court started granting bail to those convicted under martial law. Lahore High Court’s Justice Samdani granted bail to Zulfikar Ali Bhutto. Every 8 to 10 years, attempts are made to subjugate the judiciary. A law was introduced to deregister the Pakistan Peoples Party (PPP), but after Supreme Court intervention, that law was repealed. The judiciary can review any law in the context of fundamental rights at any time.”

Justice Ameenuddin, addressing Salman Akram Raja, said, “You are contradicting your own arguments.”

Salman Raja replied, “You need to establish the correct law.”

Justice Ameenuddin remarked, “We are hearing an appeal against a decision.”

Salman Raja insisted, “You need to frame the right law and interpret the Constitution correctly. Even in an appeal, the bench has jurisdiction under Article 184(3) of the Constitution.”

Justice Jamal Khan Mandokhail stated, “We are also human; we can correct our mistakes.”

After this, the court took a recess.

When the hearing resumed, Justice Naeem Akhtar Afghan addressed Salman Akram Raja, saying, “You are representing a convicted person. Are you arguing against the law itself, or are you seeking to protect your client’s fundamental rights?”

Salman Akram Raja responded, “I want both—the law to be declared void and fundamental rights to be protected.”

Justice Naeem Akhtar Afghan remarked, “You can define ‘person’ however you like. Earlier, it was about a retired officer; now, all are civilians.”

Justice Musarrat Hilali asked Salman Akram Raja, “Do civilians include people like me, or does this also apply to retired military personnel?”

Justice Jamal Khan Mandokhail, addressing Salman Akram Raja, said, “Look at what is happening in the world. May Allah make you an MNA, then you can present a bill in the assembly.”

He then asked, “In this appeal, can we exercise our authority under Article 187?”

Salman Akram Raja argued, “Under Article 187, the court always retains the power to ensure complete justice.”

Justice Ameenuddin remarked, “At the beginning, you objected to the court’s jurisdiction. Thankfully, you have now expanded it.”

Salman Akram Raja responded, “Judicial jurisdiction has always expanded over time.”

Justice Muhammad Ali Mazhar stated, “The Army Act applies when a civilian tries to incite armed personnel. Does Article 10-A apply only to civilians, or does it extend to military personnel as well?”

Justice Jamal Khan Mandokhail commented, “Until we understand the foundation of the Army Act, we will keep debating. Civil servants are punished for misconduct, and their cases are referred to anti-corruption courts.”

He further instructed Salman Akram Raja, “Stay focused on your case. We will address other questions when relevant cases arise.”

Salman Akram Raja argued, “The benefits of Article 175(3) should be extended to both civilians and armed forces personnel.”

Justice Syed Hassan Azhar Rizvi remarked, “Some enemy countries use civilians for their agendas. If we strike down Sections 2(1)(d)(1) and 2(1)(d)(2) of the Army Act, even those working for enemy agencies will not be subjected to military trials. Where would their trial take place then?”

Justice Musarrat Hilali questioned, “What procedure has been adopted in Pakistan?”

Justice Muhammad Ali Mazhar stated, “In India, court-martial procedures are similar to Pakistan’s, except that they allow appeals. Many offenses fall under court-martial jurisdiction.”

Justice Musarrat Hilali asked, “After a court-martial, where does the appeal go?”

Salman Akram Raja responded, “The appeal goes to the Army Chief. In the Court of Appeal, the Army Chief or officers nominated by him hear the case. If a sentence is awarded under Islamic law, only Muslim officers will be part of the appeal process.”

He concluded, “I would like to present a comparative analysis of the Indian Army Act and Pakistan’s Army Act.”

It is not possible for an SHO to hold a court himself, for an SP to hear the appeal, and for the IG to approve it. In India, appeals against military trials go to a tribunal, which can also grant bail during the appeal process, and the right to a fair trial is ensured.

Justice Muhammad Ali Mazhar remarked, “Does India’s Army Act contain sections 1(d)(1) and 2(d)(2)?” To this, Salman Akram Raja responded that these provisions do not exist in India. Justice Mazhar then asked, “If these provisions do not exist, how can you draw a comparative analysis? Our law is different, and India’s law is different.”

Justice Jamal Khan Mandokhail stated, “Both civilians and military personnel are citizens of Pakistan. Can even a serious crime like terrorism be tried in a military court?” He further asked, “Is the right to appeal a fundamental right?”

Salman Akram Raja responded, “The Army Chief levels the allegations, then convenes the court-martial, and the judge advocate general—all are under his command.”

Justice Mandokhail stated, “A fair trial includes an independent judge.” He also mentioned, “Regarding the ordinance issued in 1967, no decision has been made about whether it was right or wrong.”

Salman Akram Raja argued, “An FIR was filed against me on November 26, 2024, stating that I planned to run over and martyr three Rangers personnel with a vehicle. This law is for those whom the government wants to arrest. On February 7, I can be arrested. I am being told to stop speaking on TV because my case is being sent to a military court.”

Justice Mandokhail remarked, “The law was made to maintain discipline in the armed forces.”

Salman Akram Raja insisted, “It is not possible under any circumstances for a civilian to be tried in a military court.”

Justice Amin-ud-Din Khan stated, “If a law is being misused, that alone is not a basis for declaring it void. The blasphemy law was also being misused, so an SP-level officer was assigned to investigate. If a soldier and an ordinary citizen commit the same crime, how can they be tried in different courts?”

Salman Akram Raja argued, “Those who joined the military surrendered their fundamental rights, but they cannot be equated with others. No matter how serious the allegation, the trial should take place in an independent forum.”

He further stated, “My client, Arzam Junaid, was sentenced to six years by a military court. He is a first-class cricketer from Lahore and was subjected to inhumane treatment while in military custody. If I reveal details in an open court, it will seem dramatized. In military courts, appeals go to the Army Chief, under whose orders the court-martial is conducted in the first place. Even a session judge had to order that my client be allowed to sign a power of attorney for legal representation. No justification was given for why my client was placed in military custody.”

Salman Akram Raja asked, “Is it due process that the appeal goes to the same authority that initiated the trial?”

He further stated, “I will now present arguments based on five or six rulings, including those of Sharaf Afridi, Mehram Ali, and Riaz-ul-Haq.”

Later, the constitutional bench adjourned the hearing of the review petitions against the trial of civilians in military courts until Monday, February 10. Salman Akram Raja will continue his arguments on Monday.